Group 8: Beauty in Resilience

About the Exhibit

As you journey through the exhibit, we offer a guiding question:

How does one read the cultural and artistic representations of and by refugees through a critical refugee studies lens?

With the refugee story, an emphasis on the sensational and spectacular is favored, an emphasis that forecloses analyses of the global historical conditions that produce the “crisis” and impel refugee movement in the first instance. Critical Refugee Studies, or CRS, instead urges an emphasis on lived lives – how refugees have created their worlds and made meaning for themselves. This project aims to dispel narratives perpetuated by the common refugee representations in global media by contrasting refugee depictions in Greco-Roman antiquity and their representational politics, with refugee art from the Vietnam War.

Many of the following artifacts showcase the missing frames of war, imperialism, and militarization that structure the conditions of global displacement—and our complicity with such processes. Displaced from view are the invisible relations of power that broker how we see and consume the refugee subject. While refugees are ubiquitous in mainstream culture and media, they signal very little beyond the fact of their suffering.

Violin of Lê Trị

GUIDING QUESTIONS

-

How is the lived experience of Lê Trị illuminated through his violin?

-

How can we see a deeper understanding of the human spirit through Lê Trị's story?

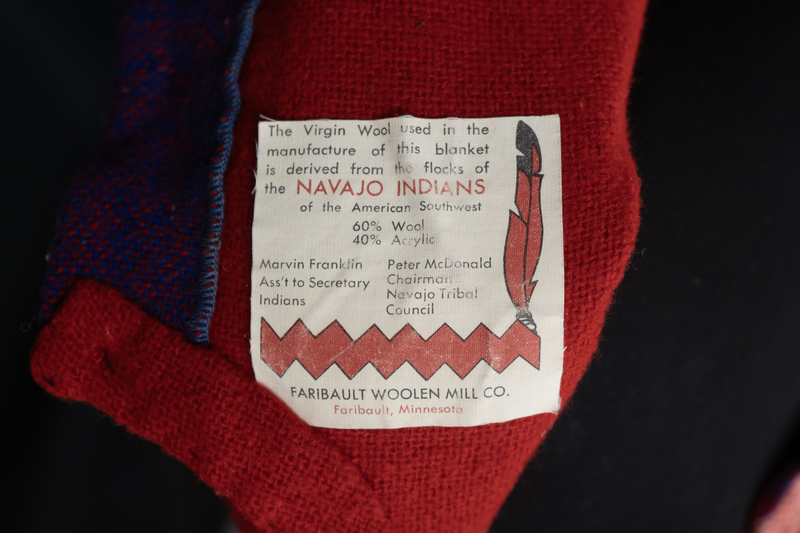

Sweater of Ms. Nguyễn Thu Nhi

GUIDING QUESTIONS

-

How does this sweater act to continue or work against the savior narrative that often accompanies US imperialism?

-

What connections can you make between the source of material being from the Navajo Tribe and being utilized by Nguyễn Thu Nhi, a Vietnamese refugee?

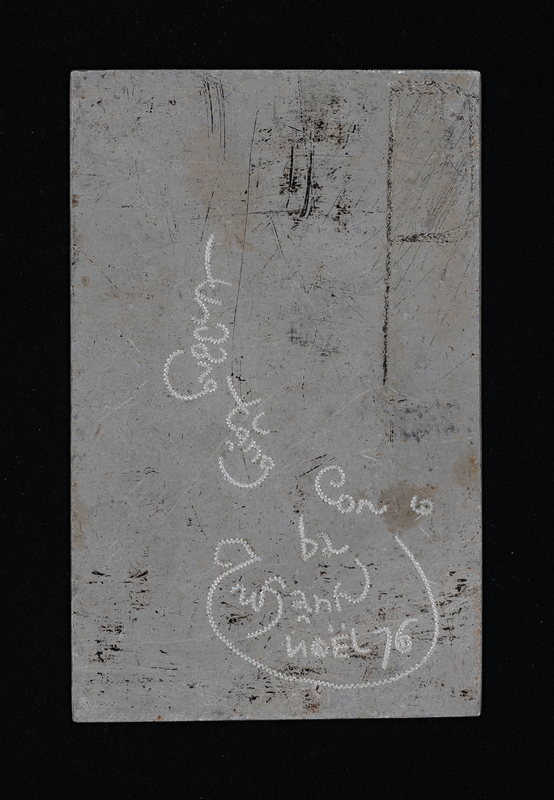

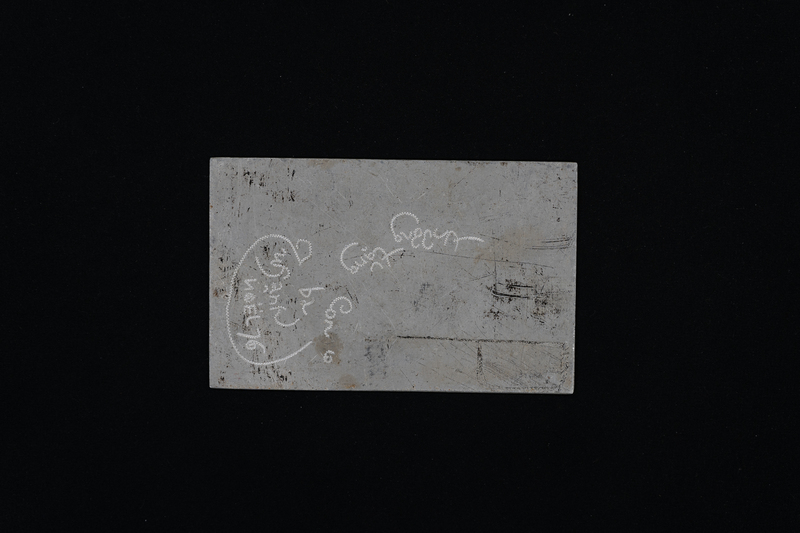

Birthday Card for Daughter of Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh

GUIDING QUESTIONS

-

How does the act of carving the aluminum piece serve as a form of resistance against the forces oppressing Mr. Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh?

-

What role does solidarity among prisoners play in this story, and how might this reflect the broader sense of community among refugees?

-

How does the act of sending a gift through a prison visitor underscore the challenges of communication for refugees separated from their families?

-

How does the father's creation of a handmade gift serve as an expression of love and a means of preserving cultural and familial connections?

-

In what ways do refugees or prisoners find creative outlets to cope with their circumstances and maintain their identities?

The Aluminum Birthday Piece For My Daughter (English Translation)

The Aluminum Birthday Piece For My Daughter

Words for daddy‘s little girl

"My heart suddenly remembered my only daughters’ birthday was quickly approaching. Daddy did not know what to give you. In prison, everyone worked incredibly hard, but they were fed a simple meal just enough for survival, a small rice bowl and some vegetable soup. I had the intention to trade my lunch with my friend in exchange for a thin piece of aluminum to make a gift for your birthday. I would engrave some art and a few words to wish you a happy birthday full of luck. That day, I only drank a liter of cold water instead of consuming any food, and the thought of your birthday was enough to fight my state of starvation. In this prison, everyone was always hungry due to the lack of food. If anyone shared a spoonful of rice with someone else, they were so touched by this gesture that tears fell.

Because of you, I could not die. I undoubtedly would return home to teach you the things that your mother was unable to because of our family’s deprivation and struggles. And only people in the same situation could understand each other through tribulations. Darling, if only you knew how touched I was when my friend not only gave me the piece of aluminum – which was more precious than gold at that time – but also advised me that, “Just take this piece and start carving it for your daughter. As a gift from me, don’t try to exchange anything. Without this cup of rice, will you be able to survive to see tomorrow?”

"I had to ask a prison visitor to bring back this gift to my daughter. Even though I thought it would have been difficult to reach her, I found out that it was being displayed in the small curio at our house like a miracle half a year later."

--- Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh

Translated by Khanh Lê and Từ Ái

Thiệp Sinh Nhật Con Gái (Vietnamese)

Miếng Nhôm – Thiệp Sinh Nhật Con Gái.

Lời Cho Con

Lòng ba chợt nhớ đến sinh nhật của con gái duy nhất sắp đến, ba chẳng biết có gì tặng con. Trong tù làm việc rất vất vả, về trại mỗi bữa ăn lưng bát cơm với bát canh rau qua ngày. Ba đã có ý định đổi phần ăn trưa với người bạn để có miếng nhôm mỏng làm tặng vật cho sinh nhật của con, ba sẽ khắc hình, có vài lời chúc con yêu “Sinh nhật vui vẻ và may mắn”. Hôm đó ba chỉ uống một lít nước lạnh trừ cơm, nhưng chỉ nghĩ đến sinh nhật của con đã giúp cho ba vượt qua cơn đói. Trong này ai cũng đói vì phần ăn quá ít ỏi, chỉ cần người này vớt cho người kia một muỗng cơm là nước mắt họ sẽ trào ra vì cảm động.

Vì con gái nên ba không thể chết được, ba nhất định sẽ trở về để dạy cho con nhiều điều mà có thể Mẹ con vì quá vất vả trong cuộc sống nên quên dạy.

Và tình đồng đội chỉ có thể hiểu nhau qua hoạn nạn. Con biết không, ba rất cảm động vì bạn của ba không những tặng cho ba miếng nhôm, một thứ quý hơn vàng lúc đó mà còn khuyên một câu chí tình nữa, “Ông cứ lấy mà khắc tặng cháu, xem như món quà sinh nhật của tôi, việc chi mà nhịn đói để đổi chác, thiếu chén cơm này liệu ngày mai ông có lết nỗi không chứ?”

Món quà Sinh Nhật này ba đã nhờ một người đi thăm nuôi mang về cho con, tưởng khó đến tay con nhưng đến nửa năm sau ba mới biết nó đang nằm trong tủ kính bé nhỏ ở nhà như một ơn lạ.

---Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh

ARTIFACT DESCRIPTION

Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh was a reeducation camp prisoner when he created this birthday card for his daughter. It was made with a thin piece of aluminum and he carved on it a few words to wish his daughter a happy birthday full of luck.

In addition to this birthday card, Mr. Hanh also created the Handmade Comb and Razor that he donated to the Vietnamese Heritage Museum. The items are displayed in chronological order by time of creation in the reeducation camp. Think about how this continuity impacts the storytelling ability of these objects when perceived together.

RELATIONSHIP TO OUR THEME

This birthday card is a reflection of the resilience of Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh through his determination to create a meaningful birthday gift for his daughter despite the harsh conditions he faced. This act of finding beauty in celebrating his loved ones is an act of resilience itself against his oppressors. We can learn a lot from this letter about the conditions in concentration camps, the solidarity amongst prisoners and the creativity that refugees turned to during difficult times.

Comb of Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh

GUIDING QUESTIONS

-

How does the religious imagery on the comb reflect the creator's faith and provide comfort in difficult times?

-

In what ways do the engraved initials of the family members serve as a testament to the creator's love and connection to his family?

-

How might the act of crafting this comb have provided the creator with a sense of purpose and resilience during his imprisonment?

-

How do personal artifacts like this comb challenge the typical narrative of refugees being solely dependent and victimized?

ARTIFACT DESCRIPTION

Handmade aluminum comb featuring engravings of religious (Catholic/Christian) imagery and the initials of three family members: the creator, his wife, and their daughter.

RELATIONSHIP TO OUR THEME

This comb exemplifies the resilience and personal agency of refugees in creating meaningful objects that reflect their identities and histories. By including religious imagery and family initials, the creator asserts his cultural and familial connections, resisting the erasure of his identity under oppressive circumstances. The comb challenges the typical portrayal of refugees as mere victims by highlighting the creator's ability to produce art that holds deep personal and cultural significance. This narrative aligns with our exhibit's aim to dispel common representations of refugees by showcasing their lived experiences and the ways they find meaning and beauty in their lives despite hardship.

Razor of Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh

GUIDING QUESTIONS

-

What does the story behind the razor reveal about the mental and emotional struggles faced by refugees and prisoners?

-

How did the creator's contemplation of using the razor to end his life highlight the depth of his despair, and what does his decision to live for his family signify about his resilience?

-

How can this razor serve as a symbol of both the dire circumstances and the unwavering hope experienced by the creator?

ARTIFACT DESCRIPTION

Aluminum folding razor with intricate hand-carved details, including floral motifs on the handle and a geometric pattern on the back edge of the blade. The creator, paralyzed in his legs from overwork and malnutrition, crafted this razor with the intent to symbolically end his life "meaningfully, beautifully, and heroically" on the anniversary of the April 30th, which marked the end of the Vietnam War. Ultimately, he was dissuaded by the thought of his family.

RELATIONSHIP TO OUR THEME

The razor crafted by Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh embodies the extreme conditions and emotional turmoil faced by refugees and prisoners. The intricate designs on the razor not only showcase his artistic talent but also reflect his desire to maintain a sense of beauty and purpose despite severe adversity. His initial intent to use the razor to end his life on a symbolic date underscores the profound impact of displacement and suffering. However, his ultimate decision to live for his family highlights the resilience and hope that refugees can cling to even in the darkest times. This artifact contributes to our theme by illustrating the complex realities of refugee experiences and challenging the one-dimensional narratives often seen in mainstream media.

Greco-Roman Antiquity

The Greco-Roman civilization, as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were directly and intimately influenced by the language, culture, government and religion of the Greeks and Romans. A better-known term is classical antiquity.

This Greco-Roman cultural foundation has been immensely influential on the language, politics, law, educational systems, philosophy, science, warfare, literature, historiography, ethics, rhetoric, art and architecture of both the Western, and through it, the modern world.

Studying artifacts from classical antiquity is important to help us better understand the the evolution of cultral representations of refugees throughout time.

Explore these artifacts and passages from Vergil's Aeneid to learn more.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

- How does knowing the creation history of a object alter its significance?

- How does Critical Refugee Studies provide a different perspective on refugee artifacts compared to traditional media narratives?

- In what ways can artifacts represent agency rather than victimhood?

Coins of Augustus

ARTIFACT DESCRIPTION

Gold coin. (whole)

Head of Augustus (Octavian) right; before, inscription; behind, inscription. Border of dots. (obverse)

Aeneas carrying Anchises on left shoulder; on right, inscription; on left, inscription. Border of dots. (reverse)

The different sides of Roman coins, called the obverse and reverse, often featured images that conveyed a variety of messages:

Obverse

The "heads side" of the coin, which usually depicted a portrait of a Roman emperor, leader, or family member in profile, along with descriptive text. The image could represent an important event the leader led, and the reverse side of the coin could depict that event. For example, Julius Caesar was the first to put his own accurate portrait on his coins.

Reverse

The "tail side" of the coin, which could feature a variety of images, including:

Architecture: Images of ancient temples, military fortifications, and public buildings could celebrate Roman religion, honor gods and goddesses, or connect the emperor to a deity.

Symbols: Symbols could represent messages such as freedom, suffering, or independence.

Battle scenes: Images of battle scenes could convey a backstory or reasoning for the coin.

Religious messages: Images could convey religious messages.

Other images: Other images could include ships, portraits, animals, legends, allegories, captives, divinities, or former revered emperors.

Coins were also used as a means of propaganda. For example, Caesar issued coins during his campaign against Pompey that featured images of Venus or Aeneas to associate himself with his divine ancestors.

In addition to the images on the front and back of the coin, a code on the coin could also identify the city that minted it, providing historical insight into the Roman Empire.

RELATIONSHIP TO OUR THEME

This specific gold coin, with Augustus on the obverse and Aeneas carrying Anchises on the reverse, serves as a powerful piece of propaganda. By depicting Aeneas, a legendary refugee who founded Rome, Augustus ties his lineage to divine origins and heroic refugee narratives, thus legitimizing his rule and connecting it to the foundation and expansion of Rome. This use of imagery not only highlights the importance of refugeehood in Roman mythology but also links it to the concept of settler colonialism, where Augustus positions himself as a successor to Aeneas's legacy of founding and expanding an empire.

This manipulation of refugeehood narratives to serve imperial ambitions underscores the coin's role in Augustus's broader propaganda strategy, reinforcing his authority and vision for the Roman Empire. The use of such imagery on coins not only immortalizes Augustus's lineage but also serves to communicate his power and legitimacy to the Roman populace and beyond.

Gifts from Troy- Transactional Nature

Our leader also brings small tokens of our former glory, relics saved from burning Troy. With this gold cup, Anchises poured libations at the altar, and this was Priam’s finery when he judged the nations: a sacred scepter and a diadem, and robes that Trojan women toiled to weave. - The Aeneid Book 7, 243

Contextual Background

In The Aeneid, Aeneas sends his men to speak to King Latinus to ask for peace. As a gesture of goodwill and to legitimize their request, they offer Latinus the gold cup that Anchises brought with him from Troy, along with Priam’s sacred scepter and purple clothing. This act of gift-giving is steeped in the traditions and values of ancient societies, where such exchanges were crucial in diplomacy and establishing alliances.

Transactional Nature of Asylum

The exchange depicted in the passage also reflects the transactional nature that can underpin requests for asylum or peace. The expectation that refugees or petitioners offer something of value in return for safety and hospitality raises questions about the underlying motives and the genuineness of the goodwill extended. This dynamic can be seen as a critique of the conditions and expectations placed upon those seeking refuge, where humanitarian aid is contingent upon perceived benefits.

Reflecting on Representation in Refugee Art

When examining refugee art, this notion of transactional goodwill prompts us to consider the narratives and depictions of refugeehood. It asks us to think critically about how these stories are told and the potential biases or underlying messages they carry. Art that represents refugees should strive to authentically portray their experiences and humanity, avoiding reductive or utilitarian perspectives that reduce their plight to mere transactions or exchanges.

Broader Implications for Critical Refugee Studies

The passage from The Aeneid also connects to broader themes in Critical Refugee Studies (CRS). CRS emphasizes understanding refugees not merely as passive victims or burdens but as active agents with rich histories and contributions. The relics Aeneas offers—symbols of Troy's former glory—highlight the richness of cultural heritage that refugees bring with them. This perspective encourages a more nuanced understanding of refugeehood, recognizing the value and dignity of refugees beyond their immediate needs or the benefits they might provide to host countries.

Frescos at Carthage - Storytelling through Art

In this grove first, a sight appeared that eased Aeneas’ fear and let him dare to dream of safety, to have more hope in troubled times. As he scanned each detail of the giant temple, waiting for the queen, and admired the city’s fortune and its craftsmen’s skill and work, he saw the stages of the Trojan War, the battles blazoned by their fame across the world, Atreus’s sons, King Priam, and Achilles cruel to both. He stopped in tears: “Achates, what place on earth, what land isn’t steeped in what we’ve suffered? Look: it’s Priam. Here too, glory has rewards; the world weeps, and mortal matters move the heart. Let go your fear. This fame will bring some safety.” He spoke, and fed his soul on empty images, sighing heavily. Tears streamed down his face. - The Aeneid, Book 1, 450

Contextual Background

In this scene, Aeneas finds himself in Carthage, inside Juno’s Temple, where he is confronted with a mural narrating the Trojan War. This depiction of his homeland’s destruction and his people's suffering is both a source of pain and a reminder of their enduring legacy. As he observes the detailed portrayal of the war, Aeneas is moved to tears, reflecting on the universal recognition of his people's trials.

Emotional Impact and Representation

This passage highlights the deep emotional impact that such representations can have on individuals who have lived through traumatic experiences. For Aeneas, seeing the mural evokes a mix of grief and solace; it immortalizes his pain but also acknowledges the heroism and endurance of the Trojans. This duality is crucial in understanding how refugee stories are portrayed and perceived.

Relation to Refugee Art

The mural in Juno’s Temple serves as an ancient parallel to modern refugee art. It captures the essence of the Trojan War, much like how contemporary refugee art aims to document and communicate the experiences of displacement and loss. This scene from The Aeneid reminds us that the portrayal of refugeehood is not just about recounting events but also about acknowledging the emotional and psychological scars left by such experiences.

Critical Reflection on Portraying Refugeehood

This scene invites us to critically reflect on how refugeehood is depicted in art and media. The glorification of Aeneas's trauma in the mural serves as a reminder that while public recognition of suffering can be validating, it also risks simplifying or commodifying deeply personal and painful experiences. We must be mindful of the balance between honoring refugees' stories and avoiding their exploitation for artistic or political gain. The mural in Juno's Temple, while a powerful testament to Trojan endurance, also exemplifies the challenges of portraying refugeehood in a way that respects the humanity and agency of those depicted.

Artifacts Analysis and Reflection

Now that you have studied both artifacts from Vietnamese refugee history and classical antiquity, we ask that you reflect on the juxtapostion of the two sets to understand refugee narratives on a global scale.

Use these guiding questions to think about the relationship between refugee art, imperial power, media narratives, and the intersectionality bewteen displaced people throughout history.

GUIDING QUESTIONS

- What initial impression does the Aluminum Razor give without knowing its background? What about gold coin of Augustus?

- How do the stories of these objects' creator change your understanding of the artifact?

- Why is it important to consider the personal narratives behind artifacts?

- How is the narrative of the US as a benevolent rescuer constructed and maintained?

- What historical contexts and actions are often overshadowed by this narrative?

- How does this savior narrative impact the portrayal and understanding of refugees?

- What does the sweater made from a Navajo blanket symbolize about the refugee experience?

- How does this artifact critique the marginalization of internally displaced people in the US?

- In what ways does the intersection of different displaced communities highlight the complexities of refugeehood?

- How do these various artifacts and their stories help you understand the broader themes of refugeehood and representation?

- What new insights have you gained about the agency of refugees through these examples?

- How can these artifacts challenge and complicate dominant narratives about refugees and displacement?

Gold Coin of Augustus

By minting coins, Augustus effectively embedded symbols of power, divine favor, and historical legitimacy into everyday transactions. These coins served as a medium for controlled narratives, projecting the emperor's desired image and reinforcing the mythology of Rome's founding. The imagery, such as Aeneas carrying Anchises, linked Augustus to Trojan heroism and divine lineage, solidifying his authority and the empire's historical continuity. This practice highlights how artifacts can manipulate perceptions and construct identities, a strategy echoed in modern contexts.

vs.

Aluminum Artifacts

Each aluminum artifact initially appears as a simple object, but understanding its creation and purpose transforms its narrative. This direct storytelling contrasts with imperial narratives, providing a nuanced, intimate perspective on refugee experiences. Such artifacts challenge one-dimensional portrayals of refugees, emphasizing their agency and complex humanity.

Gift Giving

Refugees in Troy often gave gifts to secure goodwill and safe passage. These gifts were not merely transactions but acts of maintaining cultural heritage and seeking acceptance and safety in foreign lands. This practice underscores the importance of cultural artifacts in negotiating refugee identities and securing their place within host communities. Simmillarly, Bắc Phong Từ Võ Hạnh imbued his culture and identity into the gifts designed for his wife and daughter, in order to preserve his own sense of identity in a place that stirps you of creativity, and agency.

vs.

US Savior Narrative

The narrative of the US as a benevolent rescuer enhances its self-image while overshadowing its own history of internal displacement and colonization. This dynamic is evident in the story of the Vietnamese refugee's sweater, crafted from a Navajo blanket. This artifact reflects her journey in a US refugee camp and symbolizes the intersection of different displaced communities. It critiques the marginalization of internally displaced people, like Native Americans, and highlights the transactional nature of US refugee policies, questioning the genuine goodwill behind asylum provisions.

vs.

Agency

Understanding the creation of the razor and its intended use changes its perception from a mundane item to a powerful symbol of personal and collective resistance. This shift exemplifies how refugee artifacts can reclaim narratives from imperialist representations, focusing on lived experiences and individual agency rather than victimhood.

vs.

Vietnamese Refugee Experience

Constructed from a Navajo blanket, the sweater symbolizes the intersection of Vietnamese and Native American displacement. It critiques the marginalization of internally displaced people in the US, often overshadowed by the narrative of international refugees. This artifact highlights the transactional nature of refugee status in the US, where gratitude is expected, masking the country's history of displacement and colonization. It challenges the simplistic savior narrative and underscores the complex realities of refugee experiences.

Conclusion

Through the artifacts displayed we have delved into the heart of a community that has endured immense hardships and yet emerged with an unwavering spirit.

These artifacts and stories remind us of the shared humanity that connects us all and asks us to reflect on how we consume media about refugees. Often efforts to “humanize” refugees begins to turn them into symbols of victimhood or present them as incapable. Yet it is the complete opposite, as we have seen through these artifacts.

We also want to acknowledge the lack of framework around how countries like the United States are complicit in creating the conditions of global displacement through war, militarization, and its imperialistic nature.