Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Did Egyptian art inspire Christian art and even modern photography? This podcast is meant to explore the mother and child iconography type throughout different cultures, religions, and times. The discussion starts by describing the statue of Isis and Horus and then moves onto multiforms of it, including Coptic Orthodox depictions of Mary and Jesus, Renaissance variations of Madonna and Child, and more modern examples. Listen to learn and solve the riddle embedded within the podcast!

Also featured:

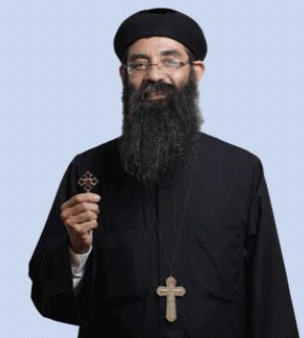

Coptic Priest

PhD Candidate, UCLA

Not pictured: Sofia McConnell

Transcript

[Intro music plays]

Section 1: Introduction (0:11)

Alysa: Welcome to the Now as Then podcast season 1 episode 5 “Like a Virgin: Mother and Child”. In this episode, we are going to be talking about the evolution in depictions of the image of mother and child — in specific, the icon of Isis and Horus of Pharaonic Egypt. My name is Alysa Rallistan and joining me today we have Jasmine Bishara and Mary Abdelnour focusing in on the Coptic image of mother and child.

Jasmine: Hi Alysa thank you for this great introduction! As you were saying, my name is Jasmine and today I will be joining you to talk about the representation of the image of mother and child, like the statue of Isis and Horus, but within the Coptic church from 42 AD until today.

Mary: My name is Mary and I am also going to be joining today’s discussion about the different depictions of the mother and child type throughout time and in different regions to analyze how the views on this type of image have evolved. We will also be asking a special question soon, and we will provide you with hints throughout the entire episode. Will you be able to find the answer to our question before we tell it to you in the end? Listen carefully!

Alysa: We also have Kim Phan with us today who will be talking about the transition of this mother and child image in light of the Renaissance.

Kim: What’s up, I’m Kim. We are starting off with some background and diving into Pharaonic Egypt. Then we’re going to explore the Coptic angle of this mother and child icon (Coptic is the Christian era of Egypt for those of you who don’t know), hop on over to Europe and see how it developed there and then talk about some more modern examples! Hopefully in the end, we will see how by itself, the icon is nothing more than a figure or an image, but when it is adopted by various groups with distinct cultural, religious and social views, it can be depicted differently and therefore interpreted in different ways! We hope you enjoy what we have for you. Now, let’s just jump into it!

Section 2: Ancient Egyptian Representation of the Image of Mother and Child (1:54)

Alysa: To trace back to this mother and child image, we should introduce to you the infamous bronze statuette that is dated to around the Late period of Ancient Egypt and depicts the goddess Isis sitting on a low backed throne nursing a small Horus who simply sits on her lap.1Susanna, Thomas. “A Saite Figure of Isis in the Petrie Museum.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 85, 1999, 232–235. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/3822442./

Jasmine: Yeah actually a little background that I found on the goddess Isis and her son Horus was that they were both alive during the 5th dynasty according to where their names were found in the Pyramid Texts, which stated that Isis bore her child Horus from Osiris.

Kim: If you didn’t already know, Osiris is the firstborn of the Earth god and Sky goddess and, after some family drama that we will get into later, became the Lord of the Underworld and Judge of the Dead. Horus was actually conceived after Osiris’ death and following Osiris’ resurrection because he is cool like that.2Plutarch, Isis and Osiris. Check out Now as Then: Episode 4 for more details and fun but he’s not really in the picture for this podcast so catch you later Osiris!

Jasmine: Allrighttt we’ll get back to Osiris in few minutes, but before we do so, I wanted to talk a little bit about the structural form of the statue of Isis and Horus. In this statue and actually in most statues of Isis, she is nearly always depicted in anthropomorphic form, meaning that she is given human characteristics and attributes as opposed to being depicted as a goddess. This statue shows Isis in her most beloved pose.

Mary: Yeah, specifically, the statue depicts Isis breastfeeding her son Horus. This was a very popular statue during pharaonic Egypt, and it was basically found everywhere like household altars and drawings. It was also worn by women in miniature talismans. You could really see, in each type of media on which Isis and Horus are presented, that Isis is sitting on a plain throne with her left hand on Horus’ back for support, offering her left breast to the infant. She is actually depicted that way, because of her role in Egyptian mythology as a protector.

*mystical music to cue the myth of Isis*

Once upon a time, in a land far, far away

Alysa: *car halt sounds* Weeellllll, approximately 7,767 miles away from California…

Mary: The priests of Heliopolis developed the myth of Isis. As we have mentioned before, Isis became a queen when she married the king of Egypt, Osiris. But jealous Seth, Osiris’s brother, trapped Osiris in a wooden chest, covered it in lead, threw it in the Nile, and became king. Isis searched for the chest and found it in… (Where did Isis find the body of Osiris? Stay tuned). She brought back Osiris’s body to Egypt, but angry Seth hacked Osiris into pieces and scattered them. Isis found all the pieces, put Osiris together, and got pregnant with Horus.

She hid her son and protected him until he was fully grown and could avenge his father’s death and reclaim the throne.3Tyldesley, Joyce. “Isis.” Encyclopædia Britannica , Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 29 Mar. 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/Isis-Egyptian-goddess.

*music fades out*

Kim: And that’s why, folks, she was seen as the goddess of protection and a role model for all women.

Jasmine: We can actually see a VERY clear connection to her role as a strong woman that is illustrated in her clothing. I am actually a huge fan of her horned crown that she adopted from the goddess Hathor during the Late Period of Pharaonic Egypt, which was from 712 BC to 323 BC. Not only did she get that crown from Hathor, but she also got her vulture headdress that was known to emphasize the role of goddesses as royal mothers. Meanwhile, Horus wears an amulet on his chest, which was seen as a common feature for the child gods.

*surprise music (airplane announcements sounds)*

Mary: Here is hint #1! This place was the chief harbor for the export of cedar and other valuable wood to Egypt. Eventually, it became a great trading center! 4The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Byblos.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2 Feb. 2007, www.britannica.com/place/Byblos.

*exit surprise music*

Alysa: To help our understanding of the stylistic developments and provide a more holistic view of the possible importance of the mother and child in Ancient Egyptian iconography we have PhD candidate Danielle Candelora to expand on this with her expertise…

Section 3: Interview with Danielle Candelora on Ancient Egyptian iconography (5:38)

Danielle: My name is Danielle Candelora. I’m a fifth year PhD candidate in the Near Eastern Languages and Cultures Department, and I’m specializing in Egyptian archaeology. Specifically, my dissertation research looks at immigration in the ancient world and a group of people who immigrated from what’s now Israel into northern Egypt and how they sort of adapted to life in their new home. Yeah, so I look at a lot of sort of cross-cultural issues of identity.

Kim: So, what is your knowledge of the statue of Isis and Horus?

Danielle: So, the particular form of the statue is extremely popular, especially in later periods of Egyptian history. Starting especially in the late period, you get a lot of these bronze–little small bronze statues of Isis holding Horus in some way, on her lap usually. But it kind of evolves out of a history of mother goddesses in Egypt, and so we have, even from some of the earliest periods like the pyramids, we have images of goddesses suckling the king as her son and things like that. So, it is a constantly present cultural element in Egypt that sort of gets developed over time (with the addition), especially the popularity of the myth of Horus as a child specifically as opposed to an adult male king becomes more popular, and then you see these statues becoming extremely popular as donations to temples, specifically.

Kim: Awesome. So what influence does the foreign interactions have on the portrayal of Isis and Horus in the later periods of ancient Egypt?

Danielle: Good question as well. Starting in the Second Intermediate Period which is the period I study, there is a lot of influence especially from the Near East coming into Egypt. This comes along with a lot of religious aspects, so gods from all over the place wind up in Egypt, and they get, what’s called syncretized– essentially smushed, technical term, together with Egyptian gods. So they kind of basically go like “oh, you have a god of storms and chaos, so do we. It’s obviously the same person.” Same god, that kind of thing. So, you get that happening a lot with female gods in particular as well because of course, you know, it’s pretty universal in the ancient world. Somebody’s gonna have a goddess of motherhood and birth and all that stuff. So, I think it gets more woven into the idea of Isis and Horus than having an obvious effect. I think the obvious effect comes when it gets exported from Egypt in later periods.

Kim: So, were there any different techniques introduced in the art styles and the cultural influences that we can see evolve throughout time in the later periods of Egypt?

Danielle: Even this, the way that they produce these metal statues that you guys are looking at, is originally potentially a foreign technology. So, the metal working in general is coming from outside of Egypt in much earlier periods, but they also bring in associated casting techniques– how they actually melt the metal and put them into molds and things to make this type of object; it’s foreign.

Kim: So, what identities did the ancient Egyptians derive and associate from the Isis and Horus icon?

Danielle: Sure. In this one you can talk about several different levels of society and their identities. So I already mentioned the king: he specifically gets associated with baby Horus, so he is like the living embodiment of Horus on Earth. The identity that he derives is basically demonstrating that he is a god and he’s being suckled by his goddess mother and things like that. In general, Isis was the mother goddess, right? So like anyone who wanted kids or whose kid was sick or anything like that was very invested in the Isis and Horus icon, which is why it is so popular as a temple dedication.

Kim: That’s so cool. Thank you. When the statue and the icon was exported out of Europe– excuse me, Egypt– into Europe or like other Near Eastern countries, what identities transferred? Were the identities the same or did it evolve into the culture itself?

Danielle: That’s a great question. So, it depends where it goes. In places where the concept of a divine king is already present, it kind of keeps that essence where Horus is identified with the child king. But in places like Greece, for example, where that is not necessarily something that is in their cultural tradition, they go more in the motherhood aspect. So, it is very adoptable,– adaptable, in both ways. Even when the Ptolemaic Dynasty starts in Egypt. So, these are Grecoo-Macedonian people who come after Alexander the Great, they adopt their cuckoo for Isis. And Cleopatra, a fame, actually paraded herself around Alexandria dressed as Isis and stuff like this. So, she is like really heavily responsible for the popularity of the Isis cult, especially abroad in Rome, because people sort of get this mixed up with, just in the same way that we have a little bit of Egyptomania today, the Romans had this as well. So, everything-Egypt was cool in Rome. And, so the Isis cult became very popular in places like Rome for that reason as well.

Alysa: That’s it for me.

Kim: I have no more questions. Do you have any closing remarks?

Danielle: No. Great project.

Kim and Alysa: Thank you.

Alysa: So as time continues from the Late Period, both figures –Isis and Horus– came to embody separate things. Isis was said to be a physical manifestation of divine motherhood with her life nurturing capabilities while Horus became closely associated with the pharaoh who believed himself to be a divine heir. SO it makes sense that the pharaoh would come to physically embody the young figure Horus. And together, these two figures made the statue an iconic religious piece throughout Ancient Egyptian households of the Late Dynastic Period.5Rosenau, Helen. “The Prototype of the Virgin and Child in the Book of Kells.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 83, no. 486, 1943, 228–231. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/868708.

Jasmine: Exactly! And in addition to that, I remember reading an article on the statue of Isis and Horus on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website that mentioned that these types of statuettes were usually dedicated not just to Isis cults, but seemingly to many temples and shrines that were built for people to worship Osiris and his child god Horus.

Although many of the cultures that followed the pharaonic era set the statue of Isis and Horus as their model and depicted it in unique and cool ways, after digging up in the older pharaonic kingdoms, we found an older statue portraying the same theme of mother and child from the Old Kingdom!6“Isis and Horus, 664–30 B.C.” Metmuseum.org, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/545969.

Alysa: So that would mean that this statue was prior to the time of the Isis and Horus statuette from the Late Dynastic Period!

Jasmine: To be specific, the statue actually belonged to King Pepi II and his mother, queen Ankhesenpepi I.

Mary: *laughing* Sounds like a mouthful.

Jasmine: Yeah! *laughing* Mary, do you know anything about King Pepi II’s reign?

Mary: Well it seems that he reigned for 90 years! He must’ve been ancient!(ba dum tss) But that’s also because he became king at age 6!

Jasmine: Oh my god! Wow! I didn’t know he was THAT young. Now that I am thinking about it, he is actually significantly smaller than his mother in the statue, and that’s probably because the sculptor wanted to highlight the fact that he reigned at such a young age.

We also see the theme of the motherly support making a second appearance here, where Pepi’s right hand is firmly closed while his left-hand rests on his mother’s hand as her left hand supports his back.

Kim: Wait, hold up. Is that a hole in the queen’s forehead? Excuse me?

Jasmine: Oh yeah about that, Egyptologists actually think this hole indicates that an object of another material was inserted in the statue. Ankhesenpepi I’s head is covered by the vulture headdress, which we have seen before in statues of the goddesses and queens who are mothers, like in the statue of Isis and Horus. Therefore, it’s probably safe to assume that the missing object could have been the head of the vulture.7Kinnaer, Jacques. “The Ancient Egypt Site.” Pepi II and His Mother | The Ancient Egypt Site , 14 May 2014, www.ancient-egypt.org/history/old-kingdom/6th-dynasty/pepi-ii/statuary-of-pepi-ii/pepi-i i-and-his-mother.html.

Kim: Wow I wonder what the object was made out of if it was taken so easily?

Mary: Oh my god! Do you think it was some form of rare jewelry that got stolen?

Jasmine: Before we get too busy looking into this scandal, let’s look into more icons that made an appearance after the pharaonic era!

Section 4: Coptic Representations of the Image of Mother and Child (14:22)

Kim: Ancient Egyptian religion and Christianity are very closely related. There is a holy trinity which in Christianity is the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit and in ancient Egyptian religion it was Ptah, Sokaris, and Osiris in the Old Kingdom and Amun, Re, and Ptah in the New Kingdom. Osiris, Isis and Horus can be considered a trinity as well. The similarities don’t stop there. All living things and nature have a place in the universe, the soul is immortal, and an eternal afterlife that is determined by one’s behavior on Earth are all shared between the two.8Franklin, J. Jeffrey. Spirit Matters: Occult Beliefs, Alternative Religions, and the Crisis of Faith in Victorian Britain. Cornell University Press, 2018. I hope that paints a clear connection between the two religions.

Mary: *Coptic hymns play quietly in the background* The Coptic era of Egypt was also called the Christian era of Egypt. It started from around the Roman Egyptian or Byzantine Egyptian era or basically the third century. It lasted approximately to the 9th century when the majority of the Egyptian population was Christian. This change was due to emperor Constantine who declared Christianity the legal religion of Egypt in 313 CE. Nowadays, we refer to Christian Egyptians as Copts. Despite the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 7th century and the conversion of many Copts to Islam, Coptic Christianity was still very relevant. In fact, to this day, there are Copts living in Egypt. They have preserved their roots and their culture within the religious context of their churches. They preserved the Coptic language which was the ancient Egyptian language with Greek alphabet and a couple of Demotic signs. It is still read by the clergy of the Coptic church today. They also preserved Coptic art which can be seen in icons all over the church.9Sauter, Megan. “What Is Coptic and Who Were the Copts in Ancient Egypt?” Biblical Archaeology Society, 12 Apr. 2019,

www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-near-eastern-world/what-is-c optic-and-who-were-the-copts-in-ancient-egypt/.

*hymns fade out*

Alysa: So how did this image of the mother and child differ as it was adopted in Coptic Christianity? Did the image become completely different in meaning? How does the style of the art impact its audience through this Coptic lens?

Mary: Okay well unlike the Egyptian art style that focuses on showing every part of a person’s body, Coptic iconography doesn’t aim to paint features of the person’s body but its soul.

However, both art styles are similar in the sense that there is this absence of naturalism and emotion because their pictures and icons don’t represent the world of the flesh. Instead of focusing on bodily accents like Renaissance art, sensory body parts such as the nose and ears, take a back seat in Coptic art. *car sounds*

As we will see in later depictions of the Madonna Lactans (the European depictions of the Virgin during the Renaissance) the breast is emphasized and even barren like in the Egyptian portrayal of Isis. The Coptic style just conceals all nudity and focuses more on the divinity of the Virgin rather than her maternity.10Lasareff, Victor. “Studies in the Iconography of the Virgin.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 20, no. 1, 1938, 26–65. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/3046561.

Jasmine: I think the main reason the Coptic style ensures that the icons are deprived of nudity is because they are mainly found in churches in Egypt and around many Christian communities in the Middle East that don’t normally like to show nudity in their art. This is an example of where we see how much the culture and location of the image can influence its artistic style.

Alysa: Some might say the adoption of this Isis and Horus image to Mary and Jesus can be seen as a power play. In a short interview with Egyptologist and PhD student Nicholas Brown he stated that this change in iconography suggests a colonial idea of power dynamics with the culture that adopts this image. Similarly, throughout the quarter we have been talking about this idea of Orientalism which I believe to be the case here. Orientalism is defined as the West’s patronizing representations of the eastern countries settled in the areas of Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East. Applying this concept of Orientalism to Egyptian art, Nicholas Brown noticed that the cultures or religions that have adopted/altered/appropriated the icon or whatever you want to call it, have turned an essentially pagan image into an image that fits the agenda of their religion. But can you expand more on the different aspects that is focused in on for Coptic art?

Mary: Well, the image of mother and child was brought from Egypt to the West and Byzantium through early Christian art. With time, the figures of both the Virgin and the child began to have a cold solemnity and an emphasized asceticism. Asceticism is a complicated word for just describing a way of life where a person practices abstinence from any sensual pleasures to attain a spiritual goal. These aspects manifested themselves in details such as the reduction of the breast to the utmost degree possible.11Lasareff, 1938.

*surprise music*

Here is hint #2: the Phoenician alphabet was developed there.12The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Byblos.”

*exit surprise music*

Jasmine: So after doing some research, Many images of Saint Mary and Jesus can be found today in Masr el Adeema , or Old Cairo, which is a region located on the East valley of the Nile, across from Giza where the pyramids are found. I was reading a book on Coptic iconography called Coptic Icons Volume II by Nabil Atalla that had images of mother and child icons from Coptic churches and I found that Al-Damshiria church in Old Cairo is the most diverse Coptic church in Egypt due to its inclusion of images of Saint Mary and Jesus that represent different influences.

For example, the church contains images that represent the Nubian style, where the mother and child are given darker features and the background behind them is decorated with authentic Nubian patterns. Nubian patterns and decorations usually include colorful geometric figures, mainly triangles and straight lines presented in a very simple way.

Another image found in that church represents the Persian style, with a very simple and plain background, and the mother and child are being portrayed in a slight angle.

Finally, the last image represents the Egyptian style, with its excessive use of gold for the clothing of both the mother and child, as well as portraying the frontal image of Jesus. Placing all those multiforms of the image of mother and child in one church suggests that Al-Damshiria Church’s main message behind these images is that regardless of where the image comes from or the ethnicity of its artist, they all serve the same purpose of honoring Saint Mary and Jesus. Each image on its own is simply a figure or an image that reflects the same idea by a different culture, but when this idea is adopted by various groups with different cultural, religious, and social views, it can be depicted differently to reflect the values that the culture holds, and thus, send a subtle message to the viewer that enables him or her to figure out the origin of the image and maybe even be able to relate it back to its ancient Egyptian multiform!13Atalla, Nabil. Selim. Coptic Icons. Lehnert & Landrock, 1998.

Mary: Just as the image of the Virgin and Jesus is a multiform of the statue of Isis and Horus, many other cultures have adopted the image of the Virgin and Jesus and created their own multiforms of it as well you know. The basis of the image, a mother and her child, is just you know uh a plain iconography type that– with cultural, social, and religious influences– can be depicted differently with different highlighted aspects such as maternity, virginity, familiality, etc. Despite all of this, these aspects are all present in each different depiction of the image. To help us add onto the Coptic depiction of mother and child, we brought a special guest.

Kim: Graciously joining us today is Father Isaac. Mary and Jasmine take it away!

Section 5: Interview with Father Isaac on Coptic iconography (21:31)

Father Isaac: My name is father Isaac Androus, I am a priest in Saint Peter and Saint Paul Coptic Orthodox Church located in Santa Monica in the diocese of Los Angeles. I was ordained in year 2004.

Mary: Could you describe the colors and the facial expressions of the icons like Mary and Jesus?

Father Isaac: I see, okay I am not an expert in Coptic iconography, but I can answer from my kind of general knowledge as a priest. Coptic iconography is part of the Coptic art. In our church there is three main branches of the Coptic art. There is hymnology, the way we sing and that’s in itself a sort of doctrine and teaching because we include in the process of singing all the faith and the dogma and the belief system that we have. The other part is the architecture, the way we build churches and how they reflect our faith, like for instance, in a typical Coptic church you have three doors. One in the West, one in the North, and one in the South, and they represent the Holy Trinity and how we enter from each door. So there are three areas of Coptic art, which are hymnology, and then the second one is architecture, and then the last one is iconography. So in Coptic icons, the whole idea is not that the painting, the idea is more of doctrine, teaching. That’s why if you notice the painting is not like– like a live painting, it’s not like when you paint a portrait of someone — they’re not really codes but they are standards. For instance, when you draw the picture of the Virgin Mary and the Lord Jesus, we usually put the Virgin Mary on the right hand of the Lord Jesus. You never find any Coptic icon with the Virgin Mary on the left hand because in Psalm 45 it says “the queen sits at the right hand of the king”.14From the “Book of Psalms” in the Bible, written by David the Prophet.

Also, in Coptic iconography, it’s always 2D, there is no third dimension, it’s only two dimensions. In Coptic iconography, the sky is colored in gold, not in blue. There are other color codes, for instance, the green in iconography represents evil. That’s why if you look at any icon that has Judas, they put him in green, not like the saints and the Lord Jesus. We usually use blue, white, and red for the Coptic saints. But green has a kind of a bad feel in the Coptic icon. Also in the Coptic icon we don’t draw– when we draw someone or when we write, we put face to face for the holy men. Evil is done — what is it called —

Mary: Profile?

Father Isaac: — profile, not face to face, so you don’t see the two eyes of someone that like Judas or anything. For the icon of the Virgin Mary you notice there is stars in her clothes, three stars usually. They represent her ever virginity. She is virgin before conceiving Christ, and while when she gave birth to Christ, and after, she continues to be a virgin. In our church we believe in the ever virginity of Saint Mary and we portray that in the icon. In the Coptic icon also when you look at the face, you don’t find all the parts of the face in equal size, the eyes – for instance, usually the eyes and the mouth, usually the eyes is a little smaller than the mouth, you know? But in Coptic iconography, it’s the opposite, the eyes are bigger than the mouth, and you know why that is? Because it represents wisdom. The eyes mean that those holy men and women of God have spiritual insight. The eye represents insight, and the mouth being small represents wisdom and not being talkative.

Jasmine: How do you think the congregation views the icon of Mary and Jesus and how are they used in prayers?

Father Isaac: Icons are used as part of prayers, so we look up to the icon and then — this is a natural spiritual feel, it is not like something written in the books of dogma. When they look at the picture, the icon of Saint Mary, they start talking to her naturally as someone talking to their mother. So we do not worship the icon, and we do not believe the icon is an idol or anything like that, absolutely, because sometimes we are accused of that because we give incense to the icon, and we consecrate and kiss the icon, no, the whole idea is we feel the presence of the saint through the icon, but the presence itself is a spiritual presence with us, does that make sense? So the icon itself is consecrated with Myron15Holy Myron is the oil with the highest level of sanctification in the Coptic Orthodox church. It is used to sanctify and consecrate to god the object or person that is being anointed and everything to be blessed, but it’s not as we sometimes are thought of as, worshiping the icon, no, the icon represents the presence of the saint with us, that’s why they face us when we walk into the church. You face the East, but the icons of the iconostasis16A screen bearing the icons that is very common in Orthodox churches. It separates the sanctuary from the nave and the chorus. face the West. Why do they face the West? To make you feel they are with you. So we talk to the Virgin Mary and say we love you, pray for us, in a very natural flow actually. We also light candles before the icons.

Jasmine: Thank you so much for meeting with us, that was very insightful and we learned a lot about Coptic art! Thank you for having us here.

Father Isaac: Sure, absolutely.

Section 6: Byzantine Representation of the Image of Mother and Child (27:31)

Alysa: There is a defined link between Isis and the Virgin Mary in that it has been said that the image of Isis nursing Horus is a “prototype” of the image of the Virgin Mary and child.17Rosenau, Helen. “The Prototype of the Virgin and Child in the Book of Kells.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 83, no. 486, 1943, 228–231. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/868708. The significance in this lies in the fact that this icon is one of the most recurring subjects of Egyptian art. Further analysis on the differences between these images as we closely look at the placement of the child from Horus between Isis’ legs to Jesus being held in the arms of the Virgin Mary in almost all catholic and Christian depictions of mother and child. Clearly, this shift in the child’s placement is representative of the child’s transition from being merely a youth to reverting back to an innocent baby in the eyes of Catholicism and Christianity. By the advent of Renaissance art and in light of Catholicism and Christianity, this was the most widely accepted representation of a child in their eyes.

Mary: Yeah like I said before, the iconography of Virgin Mary, during the Byzantine Empire, emphasized her virginity and holiness rather than her motherhood. The different variations in the way the mother or virgin is presented with her relationship to the child taken into account differs throughout different cultures.

Jasmine: That’s actually really cool that the artists chose to focus on one specific element for Saint Mary during the Byzantine era. Most of the other images I was looking at focused on highlighting Jesus as the center of the image. Some of those images I saw at the Getty Center in Los Angeles last week when I visited and they were super cool! One common element that I realized across a couple of the European images of mother and child was that they often portray the donors of the icon who ~ in common terms ~ sponsor the artist to draw the image, and in return the artist incorporates them into the picture, which I thought was a really cool way of advertising for the royalties during that time! The picture that stood out to me the most was the image of The Madonna and Child with Two Donors by Lorenzo Lotto, where the donors are in profile view kneeling alongside the Virgin and Jesus, with Jesus being the closest to the center of the image like in most European icons.18The Madonna and Child with Two Donors by Lorenzo Lotto, The Getty Center.

Mary: Well, there definitely have been transitions. For example, the European Madonna was progressively depicted as more human and the maternal affection became the main characteristic of her representation with Christ. But eventually, as the Roman Catholic Church came in conflict with the Eastern Orthodox Church, Renaissance artists in Northern Europe were exposed to Byzantine pictorial art. Some images depicted the Virgin detachedly holding baby Jesus, who often seems to be a small boy rather than a helpless baby. *baby sounds* These images function to underline her virginity over her maternity and, to some extent, undervalue the role that she played in Jesus’s life. Whereas, the Madonna is depicted with one breast exposed, breastfeeding baby Jesus and emphasizing her maternal function.19Puica, Ilie. “Biblical Elements in Coptic Icon.” European Journal of Science and Theology, vol. 2, no. 2, 20 Apr. 2006, 37–50.

Section 7: Renaissance/ European Representation of the Image of Mother and Child (30:20)

Alysa: As we have seen through the Coptic lens, the image of Isis and Horus developed to fit a more maternal appearance along with her holiness making the overarching motivation behind the change as a yearn for new artistic style and devoutness in religion. So let’s see how this icon develops during the wake of the Renaissance and Bronze Age. Could there be a clear motive behind the various representations?

*Ave Regina Caelorum begins to play quietly*

Alysa: The Renaissance was a time of academic, artistic, and cultural rebirth covering a period from the Middle Ages– roughly 14th century– to modernity — about 18th century. Centered in mostly Europe, the Renaissance’s influence stretched to the West and East European countries. One of the most prominent areas of the Renaissance were its grandiose art pieces — including the Madonna and child. Some of you may wonder what is the difference between the Virgin Mary and Madonna? There is none! *Ta-da! noise* They are one in the same, Madonna is just a medieval Italian translation of “my lady.”

Mary: With the Madonna, there have been many multiforms throughout different regions in Europe and different times. The focus of each icon is different because the purpose behind it varied and different aspects of it were emphasized. Early icons were revered and believed to have been capable of performing miracles; whereas, later depictions of Mary served as a reminder of biblical events.

Alysa: It is precisely in this light, that we focus heavily on the minor details of the various renditions of the Madonna and child and how their development came due to the respective cultures and societies it was adapted into. In the early years of the Renaissance and Bronze Age, specifically the early to mid 15th century, the various images of the Virgin Mary and child are almost always recognizable and connected to each other iconographically. I think we can agree that if someone were to show us a picture or some sort of representation of the Virgin Mary or Golden Madonna holding a child, most people would immediately know who was in the image and it’s context. Similarly, as stated by PhD student Nicholas Brown, Ancient Egyptian art was created for an illiterate audience to understand, with Isis and Horus statuette ancient Egyptians would have recognized these icons almost immediately, so it’s the same with the Virgin Mary and Jesus icon. Of course, there are small differences in the representations of the Virgin Mary and child whether it be their stances, the gaze of their faces, or their hand gestures whatever it may be, these differences can be attributed to regional differences.

Jasmine: In Italy, the famous Michelangelo depicted the well-known biblical event of Mary carrying the body of Jesus after his crucifixion, death, and removal from the cross, but before he was placed in the tomb, in his statue La Pieta. This was actually one of the biggest key events in the Virgin’s life, and it later became known as one of the Seven Sorrows of Mary, which is a Catholic devotional prayer. So it’s probably safe to assume that the intended audience for this statue was the Catholic European church.20ItalianRenaissance.org, “Michelangelo’s Pieta,” in ItalianRenaissance.org, July 23, 2012, http://www.italianrenaissance.org/michelangelos-pieta/.

*surprise music*

Mary: Here is hint #3: It is one of the oldest continuously inhabited towns in the world.21The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Byblos.”

*exit surprise music*

Jasmine: Another thing that was special about La Pieta is its structure, in that it is considered a multi-figured statue, which was considered very rare during the Renaissance era, although it was common for mother and child statues to be multi-figured. To be specific, this statue of mother and child is considered to be one of the first multi-figured statues during the era and was greatly admired by other Renaissance artists, like Leonardo.

Kim: Was there something kinda weird about the ratios of La Pieta?

Jasmine: That’s actually a question that puzzled a lot of artists when the statue was first released, and I believe the best explanation to it was that Michelangelo chose to depict Mary much bigger than Jesus in order to show the great support she provided him during his journey to the cross. When we compare this with the mother and child statues from the pharaonic era, we see that the mother is also often depicted bigger than her child, except her child is often a baby in those statues, but the different ratios still convey the same message to the audience of the mother providing support to her son.

Kim: Spanish-Italian artist Jusepe de Ribera’s Madonna with Child and Saint Bruno focuses on Mary’s holiness. There was a lot of debate up until the 14th century over whether Mary’s own birth was free of all sin and immaculate or not. Saint Bruno wrote about the Immaculate Conception and that was why in the 17th century Ribera chose to include Saint Bruno alongside the Immaculate Conception portrayal of Madonna and Child. This solidified the Church’s intention during Catholic Reformation and the iconography associated with the Immaculate Conception.22Perkins, Cynthia O. and James Hogg. A Study of the Iconography of Jusepe De Ribera’s Madonna with Child and Saint Bruno. Vol. 156, Institut für Anglistik Und Amerikanistik, Universität Salzburg, 1999. This image could be taken as an example of how the mother and child icon has been repurposed and utilized to push different agendas, in this case the Catholic Church’s.

Kim: Furthermore, we can follow the evolution of the relationship between Mary and Child and the audience with the Madonna of Humility which first appeared mid-1300s in early Italian paintings and persisted for the next century. Catholicism was moving away from the impersonal cult figure and focusing more on the layman. In order to be more humanized Jacopo di Cione shifted Mary from an elevated position to one that was closer to the ground. The child reaches for her breast but also glances outward to draw the audience in. He is wearing a protection amulet made of coral just like all the other Italian kids at the time.23Hecht, article on Renaissance pieces. Horus was also known to wear an amulet as well…Coincidence? I think not! Some artists like Carlo da Camerino chose to keep the regal “Queen of Heaven”, “Woman of the Apocalypse” Mary from the Middle Ages but she was still sitting down very much as a peasant would, accentuating her duality.24Ulmer, Rivka. Egyptian Cultural Icons in Midrash. W. De Gruyter, 2009. This duality reminds me of Cleopatra’s reign when she portrayed herself as Isis breastfeeding to assert her power especially when she was in a relationship with Mark Antony.25Ulmer, 2009. Nonetheless, this Madonna of Humility came to be the symbol of maternal tenderness in that time. Later though as seen in Pietro Perugino and Albrecht Durer’s renditions, the Madonna is still seated but the meaning of her being close to the Earth has changed. She was now associated with the fertile earth in less than 100 years of Di Cione’s piece.26Hecht, article on Renaissance pieces Art is incredibly subjective and individualistic so it really can be what you make of it. In this context, the Catholic Church was pushing to be more #relatable to maintain a strong following.

Jasmine: Oh my god! I didn’t know those paintings were all tied together, that’s super cool Kim!

Kim: Aww, thank you.

*surprise music*

Mary: Here’s Hint #4: The ruins today consist of the Crusader fortifications and gate; a Roman colonnade and small theatre; Phoenician ramparts, three major temples, and a necropolis; and remains of Neolithic dwellings. This place was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1984.27The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Byblos.”

*exit surprise music*

Jasmine: Going back to comparing the levels of nudity portrayed in each image, Mary, do you know what the Renaissance artists were trying to depict when portraying the Madonna with a certain level of nudity?

Mary: Between these eastern and western cultures, the depictions of Mary contained drastic differences. Arguments about her nudity rose as some claimed that it highlights the Virgin’s similarities to other women and that nudity in religious artwork has potential in evoking subconscious erotic associations. The nudity was justified through this lens of Naturalism which focused more on the style of art. Since it followed an artistic movement, it lost some of its religious value as a result. Another reason for her nudity was due to the fact that the aim of Renaissance painters was to depict a virtuous lady and a wet nurse with the aspects of her divinity being overlooked. The concept of the wet nurse was the focus of the social hierarchy. In older times, there was a hierarchy within the ranks of the balie, or the wet nurses, depending on who they worked for. The Virgin’s gamurra or robe was fashioned differently to resemble those found on the balie’s gowns to facilitate nursing with the minimum amount of undress. With such a focus on traditional and social practices, the image of the lactating Virgin lost a lot of its religious implications.28Holmes, Megan. “Disrobing the Virgin: The Madonna Lactans in Fifteenth Century Florentine Art,” in Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, eds. S. Matthews Grieco and G. Johnson, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997, 167-195.

Kim: This aversion to nursing wasn’t exclusive to Europe. The Tosefta, which is Jewish Oral Law in the 2nd century Roman Palestine, dictated that if anyone found a ring with an image of a breastfeeding mother it was to be thrown in the Dead Sea.29Ulmer, 2009.

Mary: Well that doesn’t help us if all that evidence is at the bottom of the sea. I wonder where we can find other images we haven’t talked about yet.

Section 8: Modern Representation of the Image of Mother and Child (39:04)

Alysa: Luckily, we have the UCLA Special Collections RIGHT HERE as a valuable database to uncover some more pictures!

Kim: #NotSpon but wish it was.

Jasmine: Here we have a picture from 1904 of an Egyptian mother from John Muir’s Egyptian Views Brought Home which was a photographic collection of daily activities in Egypt.

Kim: In this photo, the mother is angled slightly off to her left and is seated with her baby sleeping on her lap, facing her. She wears a beautiful, yet simple abaya, which is a long tunic dress, a long shawl covering her head and is adorned with gold, dangling earrings and two pearl necklaces. On her wrists, she wears simple wrap bracelets. Her hands are strong, firm and protective, yet still delicate and gentle when cradling her baby.

Jasmine: The way the woman is dressed reminds me of how people in Upper Egypt dress nowadays in the region Egyptians refer to as “Saeed Egypt”. Her outfit, or her saaeedy abaya, is very popular among older women and farmers’ wives. They mainly wear them when they go from the villages to the city.

Mary: The fact that Muir thought to photograph a woman sitting there with her child in her arms to encapsulate the entirety of Egyptian views shows how important the mother and child type is to the western photographer and the Egyptian culture.

Alysa: Yeah I agree. The specific mother and child image we see here has significance that is beyond the limits of a single culture — this image speaks volumes about the human experience. Here the mother has a duality in her posture; she delicately holds her child as is inherent of all mother’s, but there is a certain power in her stance and gaze that brings an aspect of divinity to her role.30Muir, John. Egyptian views brought home by John Muir. c1904. Photograph. UCLA Library Special Collections. She protects and nurtures, she’s strong yet gentle, she’s dauntless and humble. This is the essence of the mother and child that has allowed the continuance of the image through the times.

Jasmine: Wow this was such a cool example! Following along with our timeline, the most recent and impactful photographs I found that portray a mother with her child were actually taken in the 20th Century during the Great Depression. One of those photographs was taken by Dorothea Lange in 1936 after she has taken the job of Resettlement Administration, which was a New Deal agency placed to help impoverished families relocate. According to Lange, the woman she took the picture of was surrounded by 7 children inside a tent, but she focused the image on the mother and only 3 of her children. 31Phelan, Ben. “The Story of the ‘Migrant Mother.’” PBS , Public Broadcasting Service, 14 Apr. 2014, www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/stories/articles/2014/4/14/migrant-mother-dorothea-lange/.

Kim: Was there a specific reason why the picture didn’t include everyone?

Jasmine: I think Dorothea Lange was mainly trying to portray the struggles the mother was going through, and in the moment she was surrounded only by 3 children that Dorothea included in the picture. In fact, the conditions were very harsh for families who had a lot of children during that time because they were basically living in the streets for awhile. The woman in the picture, Florence Thompson, was only 32, but the image portrays her as much older than that, and that might be due to the fact that the image is displayed in black and white. Unlike the previous images that we have been looking at, the woman and her child are not glorified or highlighted as powerful people in any way. In fact, the woman looks very distressed and 2 of her children are looking away from the camera and leaning their heads on her, while her other child is asleep in her arms. Similar to the previous images; however, the position of the mother in the center of this image does indicate that she was their main source of support, regardless of the fact that she is stressed and worried about their current situation.

Alysa: You could say this picture has a commonality with the figures Isis and the Madonna in that these three are representations of a mother in her most intimate form. She is purposely placed in a way in which she is tending to her child — or children in this case– emphasizing her role as nurturer and protector of life. This and similar images evoke an intense emotional appeal from its audience by the use of both divine and human features.32Lasareff, Victor. “Studies in the Iconography of the Virgin.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 20, no. 1, 1938, 26–65. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/3046561 .

Jasmine: I think that’s exactly what Dorothea was trying to portray. This photograph later became known as the Migrant Mother, but unfortunately it is not available for display as of today, but I believe it travels around museums in the United States for art shows!

Kim: The final example is one I see everyday courtesy of my roommate Sofia McConnell.

Section 9: Interview with Sofia on Modern Images of Mother and Child (43:14)

Sofia: Um, hi. My name is Sofia. I am an Art major at UCLA. Yes.

Kim: Love it. So, when did you first come across this icon?

Sofia: I guess, because I didn’t grow up with any kind of organized religion in my household, like the Mother and Child image was really introduced to me through a family friend who’s an artist. She takes like historically significant like figures or scenes and recreates them into these paintings that she does and drawings that are, um, a little bit, um, like morbid or like strange and dark. So, a lot of like my first introductions as a child to a lot of like historically significant, um, symbols and like visuals were through her art. This one specific of, like the technically, the Mother and Child, was on the door of my mom’s bedroom when I was a young kid. So, and I would always like see it there. It was like a black ink drawing.

Kim: Nice. This icon obviously means a lot to you. You have it tattooed on your arm, it’s beautiful. So, what does it mean to you?

Sofia: Well, I guess it has like significance just as being kind of like consistent in my life as that image on the wall and being on my mom’s bedroom. But, after growing up, uh, the significance changed because of my experiences and my identity. And to me it’s more of like kind of like parent or like caretaker or like mentor, um, and then like child. And then the tattoo itself is like of that ink drawing but very specifically like freaky parent and like baby.

Kim: [laughs] Yes.

Sofia: But, uh, I wanna, I wanna foster kids and I want to work in outreach and like I kinda want to get a Master’s in Social Work . So, I kinda see myself in it. Um, yeah.

Kim: That’s beautiful. Thank you for taking time with us today, Sofia. We really appreciate it.

Sofia: Oh yeah, no problem. Thank you for asking.

Section 10: Conclusion (45:19)

Kim: Overall, with its origin placed in the times of Pharaonic Egypt, the mother and child image alone stands as a simple illustration but when it becomes adopted into societies with defined religious and cultural beliefs, the meaning of the iconography thus transforms into the biases of the viewer. Beauty or should I say meaning is in the eye of the beholder. The Mother and Child icon has been used across time from Pharaonic Egypt to modern times to declare powerful messages. The icon has been used to establish the power of one’s kingship and to elicit raw emotions to push the audience to feel a certain way whether it be about organized religion or pushing for the rejection of the nudity of nursing.

Jasmine: Exactly! And although the time periods between the images we discussed were very long, we still saw the common element of the mother providing care and support for her child, which serves to greatly highlight the mother in those images.

Mary: *surprise music* Thank you for staying tuned this entire episode. Earlier we asked you all a question, “where did Isis find the body of Osiris?” Well… do you have your answer? I know we do! Drumroll please *drumroll* Isis found the body of Osiris in Byblos! Byblos is on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, about 20 miles north of modern day Beirut, Lebanon. Would definitely love to visit there someday. Thank you all for tuning in today!

Kim: A very special thank you to Courtney Jacobs for helping us with UCLA’s Special Collections, Simon Lee for teaching us how to navigate UCLA’s libraries,

Mary: Deidre Whitmore for tech help and Tom Garbelotti from HumTech

Jasmine: Dani Candelora, Nicholas Brown

Alysa: Sofia McConnell and Father Isaac for talking with us.

Kim: Thank you again for spending time with us today! Don’t go looking for us because we won’t be here! Unless of course you want to hit that repeat button, then you are welcome back anytime. Check out all the other awesome episodes too! Peace out guys, gals and non-binary pals!

Mary: That’s all, folks!

Alysa: See you on the flipside!

Jasmine: LOL remember that time we recorded for like 20 minutes without actually pressing the record button, haha good times.

[Outro music plays]

Works Cited

Atalla, Nabil Selim. Coptic Icons. Lehnert & Landrock, 1998.

Franklin, J. Jeffrey. Spirit Matters: Occult Beliefs, Alternative Religions, and the Crisis of Faith in Victorian Britain. Cornell University Press, 2018.

Gkegkes, Ioannis D., et al. “Breastfeeding in Byzantine Icon Art.” SpringerLink, Springer-Verlag, 25 Feb. 2012, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00404-012-2252-3.

Higgins, Sabrina. “Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 3–4 (2012) 71-90.” Academia.edu, www.academia.edu/1954926/Divine_Mothers_The_Influence_of_Isis_on_the_Virgin_Mary_in_Egyptian_Lactans-Iconography_Journal_of_the_Canadian_Society_for_ Coptic_Studies_3_4_2012_71-90.

“Isis and Horus, 664–30 B.C.” Metmuseum.org, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/545969.

ItalianRenaissance.org, “Michelangelo’s Pieta,” in ItalianRenaissance.org, July 23, 2012, http://www.italianrenaissance.org/michelangelos-pieta/.

Kinnaer, Jacques. “The Ancient Egypt Site.” Pepi II and His Mother | The Ancient Egypt Site, 14 May 2014, www.ancient-egypt.org/history/old-kingdom/6th-dynasty/pepi-ii/statuary-of-pepi-ii/pepi-i i-and-his-mother.html.

Lasareff, Victor. “Studies in the Iconography of the Virgin.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 20, no. 1, 1938, 26–65. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3046561.

Lichte, Claudia. “A Newly Discovered ‘Virgin and Child’ in Würzburg.” Studies in the History of Art, vol. 65, 2004, 52–63. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42622356.

Megan Holmes, “Disrobing the Virgin: The Madonna Lactans in Fifteenth Century Florentine Art,” in Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, eds. S. Matthews Grieco and G. Johnson, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997, 167-195.

Melniciuc, Ilie. “Biblical Elements in Coptic Icon.” European Journal of Science and Theology, 20 Apr. 2006, www.ejst.tuiasi.ro/Files/06/37-50Melniciuc_Ilie.pdf.

Muir, John. Egyptian views brought home by John Muir. c1904. Photograph.

Perkins, Cynthia O., and James Hogg. A Study of the Iconography of Jusepe De Ribera’s Madonna with Child and Saint Bruno. Vol. 156, Institut für Anglistik Und Amerikanistik, Universität Salzburg, 1999.

Phelan, Ben. “The Story of the ‘Migrant Mother.’” PBS , Public Broadcasting Service, 14 Apr. 2014, www.pbs.org/wgbh/roadshow/stories/articles/2014/4/14/migrant-mother-dorothea-lange/.

Puica, Ilie. “Biblical Elements in Coptic Icon.” European Journal of Science and Theology, vol. 2, no. 2, 20 Apr. 2006, 37–50.

Rosenau, Helen. “The Prototype of the Virgin and Child in the Book of Kells.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, vol. 83, no. 486, 1943, 228–231. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/868708.

Sauter, Megan. “What Is Coptic and Who Were the Copts in Ancient Egypt?” Biblical Archaeology Society, 12 Apr. 2019, www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-near-eastern-world/what-is-c optic-and-who-were-the-copts-in-ancient-egypt/.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Byblos.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2 Feb. 2007, www.britannica.com/place/Byblos.

Thomas, Susanna. “A Saite Figure of Isis in the Petrie Museum.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 85, 1999, 232–235. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3822442.

Tyldesley, Joyce. “Isis.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 29 Mar. 2019, www.britannica.com/topic/Isis-Egyptian-goddess.

Ulmer, Rivka. Egyptian

Cultural Icons in Midrash. W. De Gruyter, 2009.

Sound Credits

4187appaloosa. Recording of baby noises. WAV file, created 3 Dec. 2016. https://freesound.org/people/4187appaloosa/sounds/369801/.

AmishRob. Recording of two consecutive car beeps. WAV file, created 2 April, 2018. https://freesound.org/people/AmishRob/sounds/423990/.

Barradeen. “Summer Coffee.” www.free-stock-music.com/barradeen-summer-coffee.html. Ghostrifter Official. “Morning Routine.” https://www.free-stock-music.com/ghostrifter-official-morning-routine.html

Klankbeeld. Recording of Ave Regina Caelorum choral. WAV file, created 12 Dec. 2013. https://freesound.org/people/klankbeeld/sounds/210514/.

Petroc_Elbaseet. “Khen Oushot with Ibrahim Ayad at St Mark Church Montreal.” Created 2015. https://soundcloud.com/search?q=khen%20oushot%20with%20ibrahim

Plasterbrain. Recording of Ta-da! In F major. WAV file, created 11 July, 2017. https://freesound.org/people/plasterbrain/sounds/397354/.

Robinhood76. “Game and Media Dings.” WAV file, created 15 July 2015. https://freesound.org/people/Robinhood76/sounds/350352/.

Waveplay_old. Recording of soft car screech. WAV file, created 14 April, 2014. https://freesound.org/s/233558/.

Zut50. Recording of group of people cheering yay. WAV file, created 4 Aug. 2012. https://freesound.org/people/zut50/sounds/162395/.